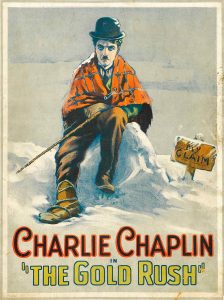

The Gold Rush

The first of Charles Chaplin’s comedy epics, The Gold Rush is a comedic marvel. In fact, Chaplin himself later stated that this was the film by which he would most like to be remembered.

Luckless prospector. The Gold Rush opens with a spectacular scene in the vicinity of Truckee, high in the Sierra Nevadas about twenty miles from Reno. Hundreds of prospectors trek up a mountain pass—Chaplin among them, slipping and sliding on the snow-covered terrain—on their gold-seeking quest through the icy pass. Unaware of a huge bear striding in his slippery tracks, Chaplin pauses to lean on his cane, which sinks to its handle in the deep snow, rendering him supine. Still followed by the bear, the unsuspecting prospector makes his way to the sheltering cabin of the villainous Black Larson (Tom Murray) who, taking rifle in hand, orders him to leave. With the best of intentions, Chaplin attempts to do so, but a raging wind keeps pushing him back into the cabin.

The same ill wind blows another prospector—a luckier one, who has found a massive gold nugget—into the cabin, the enormous Big Jim McKay (Mack Swain), who is also ordered to depart instantly. Less courteous than his fellow guest, Swain grabs for the gun; he and Murray wrestle for its possession, their choreographed struggle resulting in the gun barrel constantly pointing at the ever-evasive Chaplin, who scurries to every conceivable hiding place. Swain wins possession of the weapon, and the foodless trio decide that one of their number must depart to find provisions lest they all perish. They cut cards to determine which of them shall be the traveler; Murray, the loser, leaves. Along his way, he runs into two policemen who have been on his trail and murders them both.

Hunger. In the cabin, the two remaining famished fortune-seekers prepare their Thanksgiving day dinner: one of Chaplin’s boots, which he cooks with care in a huge pot. Serving the shoe, Chaplin severs the sole and sets it before his huge companion, who, savoring the larger part, deftly reverses their plates so that he has the upper. No matter; Chaplin makes the most of his meal, plucking the shoenails as if boning a fish, coiling the laces expertly, spaghettilike, about his fork, smacking his lips appreciatively, gourmandizing his fantasy.

Time passes; the two survivors again approach starvation. Chaplin offers his remaining boot as sustenance, but the proposed feast is refused with revulsion by his corpulent companion. Swain, maddened by hunger, begins to visualize the petite prospector as an enormous, succulent chicken; he chases Chaplin around the cabin, brandishing a huge knife. Unable to catch his agile prey, Swain goes for the gun and fires a blast, which temporarily restores him to reason. Chaplin takes the rifle and prudently buries it in the snow outside the cabin. Cut to a scene depicting the malevolent Murray, on his quest for food, stumbling upon Swain’s gold strike.

More struggle. The following morning, Swain’s delusion returns; he and Chaplin—again as a chicken—battle one another. Chaplin is blinded by a blanket that swathes his head and believes he is grappling with his fur-coated, maniacal friend; in fact, he has a death grip on the bear, which has tracked him into the cabin. The bear flees as the desperate Chaplin finds the rifle and fires. Mortally wounded, the fallen ursine visitor resolves the food-shortage problem.

Nourished again, Chaplin and Swain bid each other a friendly farewell. Swain proceeds to the site of his gold strike, where he finds the murderer, Murray. The two men fight for the mineral rights, and Swain is struck on the head, rendering him an incoherent amnesiac. Swain wanders off in a daze; Murray, savoring his victory, is suddenly visited by snowy justice in the form of an avalanche, which buries him.

Prospective romance. Meanwhile, Chaplin arrives at a gold-boom town, where he is suddenly smitten with the sight of Georgia, a beautiful dance-hall girl (Georgia Hale). Spotting an acquaintance across the crowded saloon floor, Hale sings out, “Charlie.” Enraptured, Chaplin smiles his greeting, but she proceeds past him to her same-named acquaintance. Crestfallen, Chaplin finds a torn photograph of the beauty and pockets it.

Moments later, his spirits soar again as Hale—to teach her boyfriend, Jack Cameron (Waite) a lesson—selects the sorriest specimen in the saloon, Chaplin, as a dance partner. As the two pirouette, Chaplin’s baggy trousers begin to fall. Desperately, he grabs a rope from the floor and ties it to his waist to keep his trousers up, little realizing that the opposite end serves as a collar for a huge dog. The dog gives chase to a passing cat, bringing the dance to a disastrous end. Presented with a flower by Hale, Chaplin incurs the wrath of the jealous Waite, who pulls his derby down over his eyes. The blinded Chaplin stumbles into a post, causing a clock to fall on the head of his rival. Delighted by his victory, the little gladiator takes his leave, seeking food and shelter.

Spotting Hank Curtis (Bergman) through the window of a comfortable cabin, Chaplin lies supine in the snow outside, waiting for his prospective host to emerge. Bergman spots the fallen figure, apparently frozen, and carries Chaplin inside to thaw. Bergman recruits his new-found friend as caretaker when he departs to prospect. Hale and three other dance-hall girls, out for a walk, spot Chaplin on the doorstoop and fling snowballs at him. He invites them in for a visit; as he leaves to get more firewood, Hale discovers the torn picture of herself that Chaplin had retrieved. When they depart, Chaplin invites the girls to return again for dinner and festivities on New Year’s Eve. The girls, giggling at his temerity, pretend to accept his invitation and depart. Elated, Chaplin does a dance of joy, flinging a pillow about until it bursts, filling the cabin with feathers. Needing funds to obtain the provisions for his planned feast, Chaplin decides to shovel snow for his neighbors. Cleverly, he enhances business by shoveling snow from one doorway, only to pile it up on the adjacent one.

New Year’s Eve. New Year’s Eve arrives, and Chaplin awaits his guests, his preparations meticulously made. Hearing a noise at the cabin door, he flings it open, to be greeted only by Bergman’s hungry mule, which he has forgotten to feed. He waits again. Dissolve to the cabin at the height of the festivities, the gaily attired girls exclaiming over their party favors and requesting a speech from their gracious host. Chaplin offers to dance for them instead; spearing two dinner rolls with forks, he performs a dainty dance, a pastry ballet complete with high kicks, graceful pliés, and sidewise shuffles. Enchanted by his performance, Hale kisses the little dancer, causing him to swoon with joy.

It was all a dream, of course; chastened, Chaplin awakens to the sound of gunfire. Midnight has arrived; Hale, in the saloon, has fired a brace of pistols in celebration. Suddenly remembering the invitation, Hale and the girls—with Waite in tow—decide to visit the “Little Fellow” after all. Arriving at the cabin, Hale is touched to see the party preparations. Again, she rebuffs Waite, Chaplin now her preference.

Cabin fever. Later, Swain turns up, his memory restored save only for the location of his gold strike. Spotting Chaplin in the saloon, he embraces his old friend, explaining that if they can find the old cabin, he will be able to find the gold, as well. The two set off and reach the cabin, where they spend the night.

During the darkness, a savage storm blows the cabin to the brink of an enormous abyss. Rising, Chaplin walks about, causing the cabin to teeter dangerously, rocking back and forth as it sways on the cliff’s edge. The waking Swain panics, but Chaplin reassures him, stating that the apparent swaying is simply the natural result of their previous night’s partying. Unable to see through the frosted window, Chaplin opens the door to step outside. He finds himself hanging from the door, swinging in terror over the seemingly bottomless drop. Hauled back into the cabin by Swain, the friends find themselves at a precipitous angle, clambering over one another in their efforts to reach the landward door. Swain manages to make the door; dropping, he discovers the marker to his gold claim and forgets his friend in the sliding cabin. At the last moment, however, Chaplin makes his escape, and the cabin plunges into the precipice.

Love found. Later, the gold mine having proved to be just that to the two friends, Chaplin and Swain—rich beyond the dreams of Croesus–are interviewed on board a ship by reporters. To reprise his history, Chaplin dons his old prospecting clothes. Tripping, he falls from the deck into the steerage section below, where he finds the homeward-bound Hale. As the disheveled little fellow is about to be clapped in irons as a stowaway, Hale protests that she will pay his fare. The captain and the reporters arrive to assure her that her charity case is a millionaire, and the lovers are happily reunited.

Initial interest. The Gold Rush was Chaplin’s first starring vehicle for the new distributing company, United Artists, that he had co-founded with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith six years previously (he had directed, but not starred in, UA’s A Woman of Paris in 1923). Reportedly, Chaplin came up with the idea for the picture while breakfasting with his husband-and-wife partners, Fairbanks and Pickford, who had some stereopticon pictures with scenes from the Klondike gold rush.

Chaplin also had become intensely interested in the fate of the fabled Donner party of 1846, whose tragic transcontinental trek had ended in death after their food ran out (and whose surviving members indulged in cannibalism to stay alive). Chaplin had read Charles Fayette McGlashan’s History of the Donner Party, originally published in 1879. He also might have been partly influenced by documentary director Robert Flaherty’s film Nanook of the North (1922).

Filming an epic. That the Donner story could have evoked so hilariously funny a film should come as no surprise in an industry founded on pratfalls; Chaplin well knew that “tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule.” The film was meticulously planned as a comic epic, and its cost was high (for the time), reportedly exceeding $900,000. Hundreds of extras were transported to the remote Sierra Nevada location camp at $5 a day, and Chaplin’s cinematographers shot at a twenty-five-to-one ratio, retaking until their perfectionist director was satisfied. Chaplin’s boots, which served as a meal for the protagonist and his pal Swain, were made of licorice (a natural laxative, as the already ailing Swain discovered; his revulsion at the offer of a second such meal was perfectly real), and twenty pairs were made to satisfy the outtake requirements of the picky Chaplin.

Domestic problems. The director was experiencing severe family problems during filming. He had only recently invited his mother, Hannah, to emigrate from England to live with him. Apparently senile, but with lucid moments, Hannah visited the set and saw her son illuminated by the bluish beams of Cooper-Hewitt vapor lamps in his none-too-natty working clothes. Said she, “I’ve got to get you a new suit—and you have a ghastly color. You ought to go out in the sunlight.”

But Hannah was the least of Chaplin’s domestic problems. Chaplin had initially chosen as his heroine the sixteen-year-old Lillita McMurray—who had worked with him as a child in The Kid in 1921, playing “The Angel of Temptation.” Chaplin changed her name to Lita Grey and signed her as his co-star at $75 weekly. The nubile adolescent proved to be an angel of temptation indeed; she soon became pregnant by Chaplin. Faced with her hysterical mother (to say nothing of a possible jail sentence for statutory rape), Chaplin quickly married the girl in Mexico. Some of his co-star’s scenes had already been shot, but Chaplin realized that Grey’s burgeoning belly (she was delivered of a child six months after the shotgun wedding) would rule out his young bride as the dance-hall girl if he was to keep to his planned schedule.

The heroine replaced. Lita Grey Chaplin was succeeded in the role by Hale, a one-time Miss America contestant, who had come to the attention of director Josef Von Sternberg (she had the leading role in his first helming effort, The Salvation Hunters). Chaplin had screened Von Sternberg’s film and liked it. He met Hale at a later screening and asked her to take the co-starring role in his forthcoming picture. Although Hale had already been signed for a picture by Chaplin’s good friend Fairbanks, the latter released her from the commitment as a favor to his partner.

A comedic classic. Although not all of the wildly funny sequences were entirely original (Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle had performed a dance using bread rolls in the 1918 film The Cook), they had never been performed with such grace and spirit. Years after its initial release, the film was cited by the prestigious International Film Jury as the second greatest film of all time (The Battleship Potemkin came first). To assure the film’s continuation, Chaplin reissued a version in 1941 with music and his own spoken narrative. Curiously, through an oversight, the picture’s copyright was not renewed when it lapsed in 1953. Perhaps the oversight was for the best; The Gold Rush continues to be screened, free of royalty payments, delighting audiences all over the world.

Release date: June 26, 1925

Directed by: Charlie Chaplin

Stars: Charlie Chaplin

Running time: 95 minutes

Country: United States

Language: Silent

Watch the movie online